Picture this: You’re a university student. You receive a notification to participate in a survey. You acknowledge that the survey is over 50 questions long and you have multiple deadlines coming up. But you still participated in it anyway. Why? Because you firmly believe in the power of the student voice and how small actions can lead to big changes to the academic experiences of everyone at your institution. One week later, you haven’t heard from them since. Five months later, still no response. You’ve graduated, yet you wonder whether they ever got around to fixing that broken window in the science library.

Sounds familiar?

In some cases, it might be that action was in fact taken, or at least an explanation was given, but the outcome was not explicitly linked to a specific feedback item or brought to the attention of the students who raised it in the first place. Taking action has, more often than not, been viewed as the be-all and end-all to any student issue. It is therefore no surprise that universities have generally scored low in the item “It is clear how students’ feedback on the course has been acted on.” in the National Student Survey.

This article will discuss the what, when, why, who and how’s of closing the feedback loop, with the aim of helping student reps better understand its importance and how doing it can make them better in their roles.

Once you’re comfortable with these concepts I recommend you read Unitu’s ‘Student Rep Guide’ to help you become a well-rounded rep and excel at your role.

What is it?

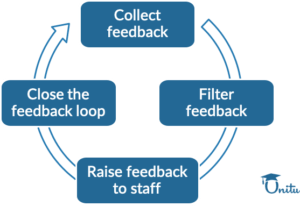

In essence, closing the feedback loop means informing relevant parties that feedback has been collected, raised and considered. It is the last stage of any feedback cycle.

Why is it important?

Closing the feedback loop is just as important as collecting it. It tells students that their voice has been heard by their elected student reps and that their opinions have been escalated to those with the authority to instigate change. Establishing a clear link between the action and the feedback improves transparency over the impact of feedback, and instills a sense of confidence in the student body, making them more willing to engage with feedback mechanisms in the future:

“‘Closing the loop’ of feedback through reporting to students any action taken by institutions tended to promote both the feeling that institutions were continually responsive to students’ concerns and that individual students were listened to when they offered feedback through official channels, such as module evaluations.”

Kandiko & Mawer (2013)

Another function of closing the feedback loop is that it can be used to test out the completeness and accuracy of the feedback given. Say for instance, you tell your department that there have been significant delays in the returning of assignments in a particular module. After informing the students that the issue has been raised (hence closing the loop), students from other modules inform you that they have been experiencing the same issue! It thus becomes apparent that this may not be a module-specific matter, but a department-wide concern.

What can I feedback?

Essentially, items that I would feed back when closing the loop include:

- Student feedback and issues that were raised

- Outcomes (such as staff responses and action points)

- Potential next steps (further research into student opinions, follow-up surveys)

- Future plans of the department.

As mentioned, it is imperative that any action or response is clearly and explicitly linked to the specific feedback that was raised.

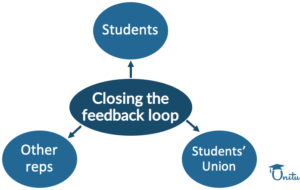

Who should I feed back to?

As a bare minimum, you should be keeping the students you represent in the loop. Even if the matter only relates to a subclass (e.g. students in a specific first-year module), it might be good practice to inform the entirety of your community, as this could allow you to pick up trends across different module and year groups.

Additionally, I think it would also be a good idea feed back to your fellow student reps and students’ union. The reasoning behind this is the same, namely to identify broader trends across different student groups and departments. Your students’ unions after all might be in a better position to investigate other departments and establish a formal task force, if necessary to address an issue. You may be informing other student reps and union officers of an issue that they have never even considered before, thereby allowing them to keep their eyes peeled in the future.

When to do it?

There isn’t really a ‘right’ time to close feedback. As a rule of thumb, the sooner after the feedback has been raised (e.g. after a meeting), the better, especially when matters are time sensitive or if students are particularly anxious about it. In any case, the students you represent should enjoy top priority in receiving information. Whilst it is also important for other student representatives and unions to be kept in the loop, for reasons detailed above, you could provide them with a summary of raised issues (as opposed to students, who might wish for timelier updates).

How to do it?

Any method of communication of preference can be at your disposal. Pre-Unitu, I used every method you could think of, from email to Facebook posts, from lecture shoutouts to Instagram stories, so that students didn’t feel fatigued with any one particular type of communication. The problem with the traditional approach of closing feedback, however, is that there will inevitably be delays and time gaps between each stage of the feedback cycle, which gives ripe opportunities for information loss and/or distortion. When we attempt to relay staff responses back to students, what students are getting is not the exact message by staff, rather an altered version of it. Moreover, there are certain elements in a message that cannot be replicated very easily, such as the tone of the staff member.

If like mine and your department subscribes to Unitu, it essentially saves student representatives the trouble of resorting to these run-of-the-mill methods, since students can clearly see staff responses when they arise, which staff posted it and which reps escalated it. In fact, a study done by Emma Mayhew on student reactions to Unitu in a University of Reading department revealed that the vast majority responded positively to the prospect of seeing exactly how staff were responding.

A Guide to Being an Effective Student Rep

If you found this article helpful, we have an in-depth guide dedicated to student reps interested in improving their skills.

Our guide breaks down a student rep’s key responsibilities and explains how you can excel at each one of them. It covers topics like collaborating with staff better, effectively collecting student feedback, consistently getting the most out of SSLC meetings, and much more.

It’s completely free and available for everyone to read. You can download the Student Rep Guide here.

Sources:

Kandiko, C. B. & Mawer, M. (2013). Student Expectations and Perceptions of Higher Education. London: King’s Learning Institute.

Mayhew, E (2019). Hearing everyone in the feedback loop: using the new discussion platform, Unitu, to enhance the staff and student dialogue. European Political Science. 18.