As part of our Closing the Feedback Loop webinar, we spoke to Dr Libby Farrier-Williams, who recently completed a PhD examining how students are co-creating value and how higher education institutions can ensure that they are working with students to provide the best opportunities and experiences.

Libby’s interest in value co-creation stemmed from her experiences as Vice President for Education and Representation at Nottingham Trent University Student Union. She recognised that University senior management often focused their attention on top-flight, engaged students and those who were at risk of failing, leaving the majority of students who fall in between those two extremes underrepresented.

What is value co-creation, and why is it important?

Value co-creation is about understanding how students engage with the University’s offerings, and finding ways to encourage that engagement. We need to understand:

- What they’re engaging with

- How they would like to engage more

- How their patterns of engagement change throughout their degree

We often misunderstand value co-creation. As staff, we can only provide offerings. It’s student engagement with those offerings, and their perception of their engagement, that actually creates value.

Value co-creation isn’t just about hearing student feedback, although that is also incredibly important. It’s about enabling agency. When students are engaged in the design and implementation of offerings, they are able to co-create value.

Embedding a student voice strategy

Libby highlighted that we need to provide opportunities to hear student voices through both formal and informal platforms, and to integrate the information coming from disparate sources. Informal platforms are often key to hearing diverse voices, which further boosts co-creation and partnership.

Understanding the University ecosystem

Universities typically focus primarily on academic relationships when looking at value creation, thinking about tutors, library spaces, and lectures. Libby highlighted that this actually represents a minority of students’ interactions.

After all, students typically spend more of their time attending clubs and societies, doing paid work or accessing support services than they do in contact with academic staff.

Student journey

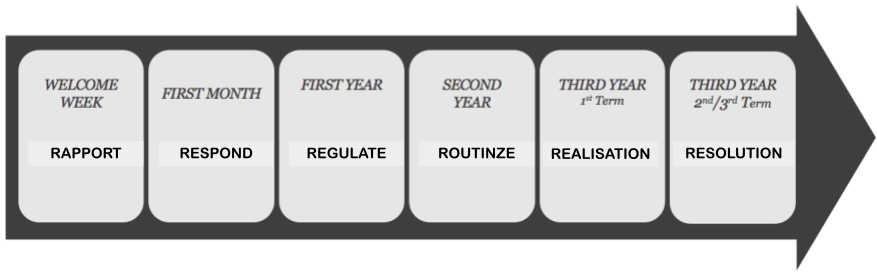

Libby divides the student journey up into 6 stages, with different priorities. Different strategies are needed to drive engagement and value co-creation at each stage.

During Freshers week, students are typically overwhelmed, and not receptive to giving feedback or looking at longer-term value creation (such as boosting employment prospects).

The first month is one of the most important stages, according to Libby. During this period, students are creating the norms and expectations that will remain with them for the rest of their student journey. Encouraging feedback and dialogue at this stage creates an expectation of engagement. Informal feedback and building trust are key at this stage.

The rest of the first year is when we can try to engage students in a more structured and comprehensive way. This includes academic committees and boards and similar.

During the second year, students typically have more demands on their time and energy and they have also built relationships and developed confidence. This can make it particularly difficult to build engagement. The few students who are keen to engage at this stage may also not be representative of the student body as a whole, so it’s essential to seek out diverse voices.

Then, within the first term of the third year, students typically have a period of realisation that their student journey is coming to an end, which leads to reengagement.

The final two terms are focused on long-term goals, such as finding employment. With such a short amount of time available, universities must respond quickly to issues raised and show that they are still engaged with this student group.

Feedback opportunities

Libby highlighted the wide variety of opportunities for students to give feedback, ranging from course evaluation surveys and course liaison committees to informal hubs and SU feedback campaigns.

She also recognised that we can’t rely on just one of these strategies. Students (and staff) can become overwhelmed with too many surveys, and different feedback opportunities will appeal to different student voices.

Examples of an academic plan

Academic staff have a great opportunity to encourage the student voice, but we need to approach it in the right way. There are lots of changes, big and small, that can help students to feel empowered and understood.

One important thing to think about, according to Libby, is the language used by tutors. Many academics use quite formal academic language, which feels professional. This creates barriers between us and the student body and can be particularly intimidating for diverse students. Using more accessible language can have a huge impact on students’ ability to engage.

She also highlighted the importance of seeking out feedback, particularly from students you might not hear from regularly:

“As they’re leaving, I find those students who haven’t said much. I go out of my way to ask how the session went and where they’re up to. You capture little pockets of where they’re struggling or what’s going wrong.”

6 Tips for Feedback Success

Communication

Providing space for shared dialogue, in both formal and informal settings is essential. It is also important that there are continuous opportunities, ensuring that students don’t feel that they’ve missed their chance to speak up.

Transparency

Being open and honest about what you, both as an individual staff member and the organisation as a whole, can and can’t do is essential for building trust. Students are looking for clarity, which can only come with trust.

Consistency

Universities need to strike a balance between consistency across departments and flexibility. A lack of consistency can lead to unmet expectations, which increases dissatisfaction.

Awareness

We can’t fix what we don’t know is broken. Listening to a wide range of voices allows us to react to the different challenges student groups face.

Agency

Providing opportunities for students to make their own choices and be proactive about their self-development can help build confidence and life skills.

Staff Development

Being responsive to student needs, especially during the pandemic, places a significant burden on academic staff. Ensuring that staff are given training and support can lead to improvements for staff and students.

Closing the feedback loop

Closing the feedback loop isn’t just about addressing student concerns. It’s about showing that you’ve understood those concerns and then communicating what you have done about them and what steps you’re taking next.

Libby suggests producing a bullet point list of areas of concern during group meetings which is then emailed to students to show you’ve understood their concerns. This can also be used to demonstrate changes you’ve made as a result, and areas where you’re still making progress.

Into the future: Going into 21/22

Looking ahead to the 21/22 academic year, Libby sees a huge opportunity. Universities can “shape a new culture in every aspect, from student voice to sexual harassment and alcohol abuse.”

Students are more engaged than ever, and that’s something universities and staff should be really excited about.